Devil-Land

A spoiler alert, if one is needed, is that despite the title of this blog, it is about a history book and not about current events in Ukraine, where ‘Devil-Land’ might well be an understatement for what is going on.

As I mentioned last week, I seem to have been taken with the urge to read some hefty historical tomes recently. The Christmas break saw me grappling with Antonia Fraser’s biography of Cromwell, which ran to nearly nine hundred pages, and the recent half-term holiday gave me the chance to finish the five hundred-plus pages of Clare Jackson’s highly impressive ‘Devil-Land: England under Siege 1588-1688’.

The title comes from the idea that the English liked to play on the name of their country to suggest it was ‘Angel-Land’, but foreigners, and particularly ambassadors and those with easier access to the centres of power, saw a very different picture. To them, the England of the late-Tudor and Stuart periods was a land of devils, misfortune and chaos. The concluding page of the book, unusually perhaps, is therefore the perfect place to start, where the author sums up her endeavours as follows: ‘Devil-Land’ has explored both the complex geopolitical entanglements and the anxious precarity of life under England’s Tudor and Stuart rulers, in order to make them better known.

She goes on to reference Jonathan Swift’s ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ (1726), where Lemuel Gulliver attempted something similar when he recounted recent events in England to the king of Brobdingnag, after which the king pronounced himself ‘perfectly astonished with the historical account I gave him of our affairs during the last century. To the king’s mind, ‘it was only a heap of conspiracies, rebellions, murders, massacres, revolutions, banishments; the very worst effects that avarice, faction, hypocrisy, perfidiousness, cruelty, rage, madness, hatred, envy, lust, malice and ambition could produce’.

At our recent Offer Holders’ Evening for those thinking of coming to the school in Year 5 or Year 7, one of the slides in my presentation explained our House system. We will need new names for our Houses, both at Radnor House and at Kneller Hall, and it is certainly time to move away from everything being named after ‘Dead White Guys’; but I have a lot of time for Pope, Swift, Voltaire and Parnell, who were prepared to satirise what they saw as the pomposity and hypocrisy of both the State and the Church in the first half of the eighteenth century. I am pretty sure they would all have been writing for Private Eye if they were alive today.

Jackson must have spent a long time in libraries and archives during the writing of her book, particularly looking at the extensive correspondence between the overseas emissaries in London, and indeed across Europe, and their various masters and mistresses in their respective native lands. As a consequence, there are a lot of unfamiliar names and a wide cast of characters in the book, but there were plenty of fascinating nuggets to keep both the general reader and those with a little more contextual knowledge interested.

For example, despite having taught the history of both the Tudor and the Stuart dynasties to A Level classes, I had not fully comprehended that between 1603 and 1700, over twenty-five of the legitimate Stuart offspring died before the age of twenty-one, with James VI & I becoming the only one of thirteen English monarchs between Henry VII and George I who lived to see a grandchild born. If my calculations are correct, he lived to see the first eight of the thirteen children of his daughter Elizabeth and her husband, Frederick V of the Palatinate.

There is a whole series of blogs to be written about whether the history we think we know is actually what happened, and I am not just talking about things like the conspiracy theories around the moon landings. For example, only a few weeks ago I was teaching Year 8 about the Spanish Armada and the apparently momentous episode when Queen Elizabeth inspected the troops at West Tilbury under the command of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester.

In a speech that came to epitomise popular memories of ‘Good Queen Bess’, I had always thought that Elizabeth said, ‘I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm.’ Jackson, however, opens a significant trapdoor of doubt by pointing out that the first printed account of her speech only appeared more than seventy years later, and no definitive record of the words spoken on the day survives, so Elizabeth’s actual turn of phrase may have been rhetorically less sparkling.

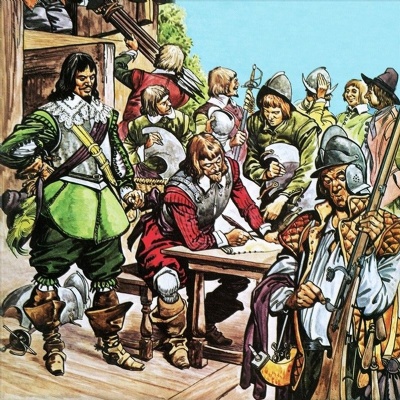

The statistics in relation to the Civil War generated plenty of food for thought, for example when Charles I’s nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine recorded in his journal that he had ridden around 5,750 miles while campaigning for his beleaguered uncle’s cause. More sobering was the notion that during the 1640s men took up arms either for or against Charles I’s authority in nearly every part of the British Isles, leading to around 200,000 military and civilian deaths in a greater loss of life in the country – as a proportion of the population – than both twentieth-century world wars combined.

There was also some interesting analysis about the short-term consequences of the Civil War and its longer-term impact. For example, for the parliamentarian commander the Earl of Manchester, the priority remained seeking a permanent peace rather than simply amassing military victories on the field. As he warned colleagues, ‘Even if we beat the king nine-and-ninety times, yet he is king still, and so will his posterity be after him; but if the king beat us once, we shall all be hanged, and our posterity made slaves.’

The war veteran Roger Boyle, Lord Broghill, warned Cromwell’s Protectorate’s ministers that internal divisions risked alienating subjects’ loyalties and provoking unforeseen outcomes. As a soldier, Broghill cautioned, ‘When we sow wheat, we know we shall reap wheat; but you statesmen, when you sow one sort of fruit, often reap another: nay, I hear some amongst you are like to reap fruit, whose seed you never sowed, neither will any own the sowing of it.’

Finally, the Act of Settlement in 1701 legally and definitively vested the English and Irish lines of succession in the Electress Sophia of Hanover and her descendants, stipulating that no future monarch could be Catholic or married to a Catholic. It was not until the Succession to the Crown Act was passed in 2013 that the Act’s terms were amended to accord male and female heirs equal rights in the line of succession, no longer disqualifying claimants married to a Catholic spouse.

We may not be very good at learning the lessons that history is prepared to teach us, but we cannot doubt that its impact continues to echo through our world, both at home and abroad, which is why we need to keep trying to understand the past as best we can – and ‘Devil-Land’ has certainly helped me with my understanding.