Another Eclectic Journey

In the weekly bulletin that went out on the final day of last term, I highlighted something that I had read in Tim Harford’s ‘The Next Fifty Things That Made the Modern Economy’, which is in effect the things from number fifty-one to one hundred that helped to develop the world as we know it. Perhaps not surprisingly, I did not think this follow up was as good as the first book, but it was still very interesting and readable, with lots of the sort of eclectic information that I enjoy gathering.

The Christmas trivia I referenced was the reminder that Santa Claus was not the creation of a 1930s advertising campaign by Coca-Cola, as is often claimed: it was Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer who was invented as a marketing gimmick. The modern Santa Claus is a century older, adapted from Dutch traditions in the once-Dutch city of New York, by prosperous Manhattanites such as Washington Irving and Clement Clarke Moore in the early 1800s. Irving and Moore also wanted to turn Christmas Eve from a raucous partying of street gangs into a hushed family affair, everyone tucked up in bed and not a creature stirring – not even a mouse.

As an economist, it is not surprising that Harford is keen to highlight the financial impact of Christmas, on which many of us may well be reflecting just now as we endure the long wait for January’s pay day. You might think that America would be the country that spends most per capita on Christmas, but you would apparently be wrong, and it turns out the December spending boom in the USA is not particularly large relative to other countries. Portugal, Italy, South Africa, Mexico and the United Kingdom have the largest Christmas retail boom relative to the size of their economies, with the Americans quite a long way back.

In the grand scheme of things, Christmas across the world is actually something of a modest affair, financially speaking. For example, Harford highlights that in the USA, for every thousand dollars spent across the year, just three dollars are specifically attributable to Christmas. After all, he says, you were going to have lunch anyway, and pay your rent, and fill your car with petrol and buy clothes to wear. For certain retail sectors, however – notably jewellery, department stores, electronics and useless tat – Christmas is a very big deal indeed. A small fraction of a big number is still a big number – at least sixty or seventy billion dollars are spent on Christmas in the USA, and perhaps two hundred billion dollars around the world.

As you may well have experienced this year, it turns out we are not actually very good at choosing gifts, with a typical hundred-dollar purchase estimated by economists to be valued at eighty-two dollars by the recipient, with one study suggesting that as much as thirty-five billion dollars are being wasted around the world each year on poorly chosen Christmas presents.

As he likes to do, Harford puts this into context by telling his readers that this is about what the World Bank lends to the governments of developing countries each year. As he concludes, this is real money, and it is really being wasted. And that is before pondering the strain put on the economy by squeezing the retail spending together into a single month rather than spreading it out across the year – and the time and aggravation devoted to the process of shopping, which is often not pleasant during the December rush. However, we will all no doubt go through the same rigmarole next year because, well, it’s what we do at Christmas, isn’t it?

Away from the bleak reality of wasted money, I enjoyed the analysis of the humble bicycle, the invention of which the geneticist Steve Jones has argued was the most important event in recent human evolution, because it finally made it easier to meet, marry and mate with someone who lived outside one’s immediate community. Harford adds that it is tempting to view the bicycle as the technology of the past, because although it created demand for better roads, and allowed manufacturers to hone their skills, it then gave way to the motor car – did it not? Apparently not, with the data clearly showing otherwise. Half a century ago, world production of bikes and cars was about the same – twenty million each per year. Production of cars may have since tripled, but production of bicycles has increased twice as fast again – to 120 million a year.

He goes on to say that it is not absurd to suggest that bicycles are pointing the way yet again. As we seem to stand on the brink of an age of self-driving cars, many people expect that the vehicle of the future will not be owned, but rented with the click of a smartphone app. If so, the vehicle of the future is here: globally well over a thousand bike-share schemes and tens of millions of dockless, easy-to-rent bikes are now thought to be in circulation, with numbers growing fast.

Around many gridlocked cities, not unlike the one in which we live, the bicycle is still the quickest way to get around. Many cyclists are discouraged only by diesel fumes and by the prospect of crashing. But, as Harford points out, if the next generation of automobile is a pollution-free electric model, driven by a cautious and considerate robot, it may be that the bicycle’s comeback is about to pick up speed, so to speak.

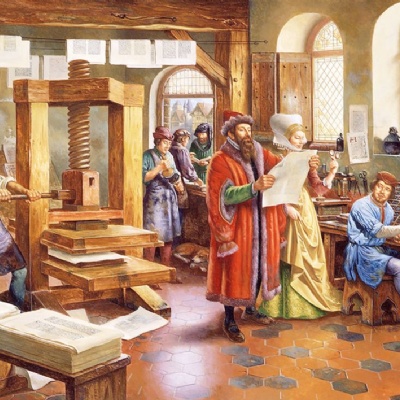

My final selection from the book to share with you is the printing press, the machine that changed the world forever in the sixteenth century. With his customary perceptive analytical skills, the author makes the point that there was nothing particularly unusual about a professor of theology like Martin Luther engaging in religious argument with the Catholic Church – and church doors were a traditional place for publicity. What was unusual was the speed with which the printing press disseminated the rebellious ideas of Luther and his followers. And with Catholic loyalists also using printing presses to publish their counter-propaganda, this not only filled the pockets of the printers but also ultimately led to the catastrophe of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48).

There is, as we are regularly reminded, nothing new under the sun, so who would have thought that a revolutionary new technology might reward inflammatory rhetoric? Modern internet trolls argue that conflict brings attention, and attention brings influence – but any German living through the seventeenth century could have attested that this is not a new idea.

According to the British Library, Johannes Gutenberg was the ‘Man of the Millennium’, and Harford asserts that there are few others whom one could nominate for such an honour with a straight face. But we are told that even the man of the millennium struggled to make money from the printing press, arguing endlessly with a succession of dodgy business partners and ending his days in relative poverty.

Concluding this week’s blog, Harford reminds us that sometimes automation creates jobs and sometimes it destroys them. The point is that automation reshapes the workplace in much subtler ways than ‘a robot took my job’. But we also need to remember that computers are only as infallible as those who programme them or use them. If we are not careful, all we do is to acquire a lever with which to magnify human error to a dramatic scale. Now there’s a cheery thought to get 2023 underway!