All Roads Lead to Bill Bryson

Picture: Peter Jackson / Bridgeman Art Library / Universal Images Group

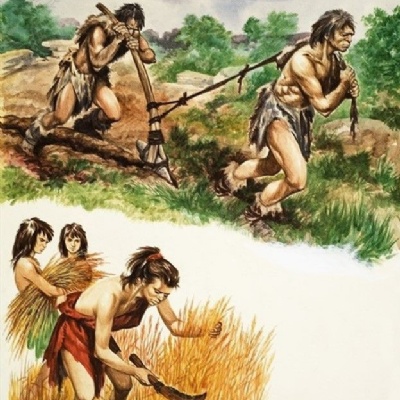

There has been a consistent theme in my recent reading about the development of societies and the inequalities and consequences that their creation brings. For example, in his history of cheese-making, Ned Palmer makes the point that he has a wider question about why anyone would take up farming in the first place. The archaeological records show that populations that made the shift to farming became less healthy, less tall, shorter-lived and began to show evidence of injuries sustained from a lifetime of repetitive toil. But he says he knows why they did it, and he is happy to dissolve this controversy: they developed a taste for beer and cheese.

It is apparently true that some prehistorians believe that people began to settle and domesticate crops so that they could brew more beer, and others contend it was the domestication of ruminant animals to get more milk for cheese that drove a move towards a farming lifestyle. And, as Palmer found out from the timeline on the wall of the visitor centre at Stonehenge, brewing and cheesemaking turned up at around the same time, well before baking. He concludes that Neolithic people had their priorities right.

My latest read is ‘Fifty Things That Made The Modern Economy’ by the always-entertaining Tim Harford, of which there may well be a lot to share in due course. As early as the first couple of pages, he made a similar point about the creation of society as we know it, saying that once agriculture began in earnest it was no longer just a desperate alternative to a dying nomadic lifestyle, but a source of real prosperity, with settled farmers proving several times more productive than the foragers they had replaced. With only a fifth of the population needed to provide food, everyone else was freed up to bake bread, fire bricks, fell trees, build houses, mine ore, smelt metals, construct roads – in other words, to make cities and build civilisation.

But Harford also highlights a paradox: more abundance can lead to more competition. If ordinary people live at subsistence levels, powerful people cannot really take much away from them – not if they want to come back and take more the next time there is a harvest. But the more that ordinary people are able to produce, the more that powerful people can confiscate. Agricultural abundance creates rulers and ruled, masters and servants, and inequality of wealth unheard of in hunter-gather societies. It enables the rise of kings and soldiers, bureaucrats and priests – to organise wisely, or live idly off the work of others. Early farming societies could be astonishingly unequal, focusing on the Roman Empire, for example, which he says seems to have been close to the biological limits of inequality: if the rich had had any more of the Empire’s resources, most people would simply have starved.

The plough is the focus of the first chapter of the fifty in the book, with the author pointing out that it did much more than increase crop yields. It changed everything, leading some to ask whether inventing the plough was entirely a good idea. Not that it did not work – it worked brilliantly – but because along with providing the underpinnings of civilisation, it seems to have enabled the rise of misogyny and tyranny. Agreeing with Palmer’s analysis, Harford says that archaeological evidence also suggests that the early farmers had far worse health than their immediate hunter-gatherer forebears.

With their diets of rice and grain, our ancestors were starved of vitamins, iron and protein. As societies switched from foraging to agriculture ten thousand years ago, the average height of both men and women shrank by around fifteen centimetres, and there is ample evidence of parasites, disease and childhood malnutrition. Jared Diamond, author of ‘Guns, Germs and Steel’, called the adoption of agriculture ‘the worst mistake in the history of the human race’.

As night follows day, so all intellectual loops seem to come back to Bill Bryson. After a couple of mixed experiences with yet more of his travel stories that sometimes lack variety, I was delighted to be transfixed by ‘The Body: A Guide For Occupants’ over the Easter break. In the section on viruses and bacteria, Bryson makes the same point about the development of agriculture, also quoting Jared Diamond, who this time called it ‘a catastrophe from which we have never recovered’.

Agreeing with what has already been established, Bryson goes on to say that, perversely, farming did not bring improved diets but almost everywhere poorer ones. Focusing on a narrower range of staple foods meant most people suffered at least some dietary deficiencies, without necessarily being aware of it. Moreover, living in proximity with domesticated animals meant that their diseases became our diseases. Leprosy, plague, tuberculosis, typhus, diphtheria, measles, influenzas – all vaulted from goats and pigs and cows and the like straight into us. By one estimate, about 60 per cent of all infectious diseases are zoonotic, i.e. from animals. Farming led to the rise of commerce and literacy and the fruits of civilisation, but also gave us millennia of rotten teeth, stunted growth and diminished health.

In his inimitable style, Bryson highlights that since the elimination of smallpox, tuberculosis is today one of the deadliest infectious diseases on the planet, with between 1.5 and 2 million people dying of it every year, even though it is a disease we have almost forgotten about, particularly in the West. More commonly, we are now prone to diseases brought on by our indolent and overindulgent modern lifestyles. We were born with the bodies of hunter-gatherers but spend our lives as couch potatoes. If we want to be healthy, we need to eat and move about a little more like our ancient ancestors did. That does not mean we have to eat tubers and hunt wildebeest, but it does mean that we should consume a lot less sugary and processed foods, in smaller amounts, and get more exercise. Failure to do so is giving us disorders like Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease that are killing us in great numbers.

Writing in 2019, when few, if any, had heard of coronavirus, he points out that it is remarkable that bad things do not happen more often. According to one estimate, the number of viruses in birds and mammals that have the potential to leap the species barrier and infect us may be as high as 800,000. He was clearly right when he says that this is a lot of potential danger, and his conclusion to this section is a sombre note on which to end: ‘We are really no better prepared for a bad outbreak of influenza or another virus than we were when Spanish flu killed tens of millions of people a hundred years ago. The reason we have not had another experience like that is not because we have been especially vigilant. It is because we have been lucky.’ Almost as soon as the ink was dry, our luck ran out.