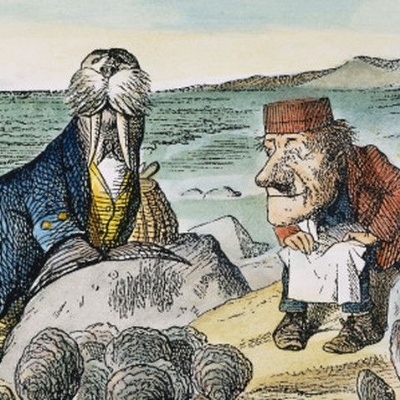

The Time Has Come

‘The time has come,' the Walrus said,

To talk of many things:

Of shoes and ships and sealing-wax,

Of cabbages and kings,

And why the sea is boiling hot,

And whether pigs have wings.'

Whether Lewis Carroll’s poem from ‘Through the Looking-Glass’ is a clever political metaphor or just another piece of nonsense from Alice’s ongoing adventures in Wonderland is not for me to decide, not least because I am not particularly bothered just now about its origins or its meaning. On the other hand, the sort of ideas that the Walrus proposes to discuss look rather more interesting to me because I enjoy an eclectic journey of fact-finding across a range of themes. However, the line that has always stuck with me, not least when I feel I may have reached a turning point, is the first one – ‘The time has come’ – with its sense that something is ending and something else is about to begin, and during the summer holiday I turned to it again as a result of a couple of books I read.

Having enjoyed Leonard Mlodinow’s book ‘The Drunkard’s Walk’ last year, I bought a copy of his latest book ‘Emotional’ in the hope of discovering another batch of interesting ideas, but unfortunately I did not find myself made much the wiser by anything he had to say about how we use our emotions to make our way in the world. Most of the themes and ideas were already familiar from other authors and I found I had seen them expressed more effectively elsewhere.

The book was not without its moments. For example, when explaining the development of our species, Mlodinow tells us that about two million years ago our ancestor Homo erectus evolved a much larger skull, which allowed for the expansion of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes of the brain. That gave us, like a new smartphone model, a great boost in our computing power. But it also caused problems because, unlike a smartphone, a brand-new human has to slide down the birth canal of an older human, and it has to be supported by the mother’s own metabolic activity until that blissful moment.

Apparently, as a result of such challenges, human babies make their exit earlier than is normal for primates – a human pregnancy would have to last eighteen months to allow the brain of a human child to be as developed as that of a chimpanzee when it is born, by which time the baby would be too large to exit the birth canal. This earlier exit solves some problems, but it causes others. Because the human brain at birth is not very well developed (only 25 per cent of adult size, as opposed to 40-50 per cent for an infant chimp), human parents are burdened with a child who will remain helpless for many years, about twice as many as a baby chimp – though some of us may think our children remain helpless for far longer than that.

Another notion that appealed to me was when the author described how, in an experiment with trading foreign exchanges, scientists found that people who were feeling sad made more accurate judgements and more realistic trading decisions than people who were feeling happy. This, we are told, is because sadness motivates us to do the difficult mental work of rethinking beliefs and reprioritising goals.

This process broadens the scope of our information processing in order to help us understand the causes and consequences of our loss or failure and the obstacles to our success. And it is geared towards reassessing our strategies and accepting new conditions that might not be desirable but that we cannot alter. The manner in which we process information when we are in a sad state helps us figure out why things are going badly and how to change course. Such thinking helps us shed unrealistic expectations and goals – leading to better outcomes.

We also learn that obesity has been estimated to cause 300,000 deaths per year in the United States alone. It is a situation that developed gradually, so that, like the proverbial frog in the pot of water that is heated ever so slowly, we failed to notice until it was too late. The availability of drugs of abuse and the advance of commercial food science have both contributed to fooling the human emotional reward system, though Mlodinow wisely observes that while science can elucidate the mechanisms through which foods addict us, it is nevertheless up to consumers to heed the warning and avoid being manipulated into obesity.

Though I have enjoyed his books and podcasts in recent years, I found myself disappointed when I got to the end of Steven Pinker’s ‘Rationality’. It had its interesting moments, for example when he tells us that lifesaving knowledge in public health, including the carcinogenicity of tobacco products, was originally discovered by Nazi scientists, which later allowed tobacco companies to reject the link between smoking and cancer for many years on the grounds that it was ‘Nazi science’.

When looking at how our fear of nuclear power may be based on irrational thinking, he makes the point that its use has stalled for decades in the United States and is being pushed back in Europe, often replaced by dirty and dangerous coal. In large part the opposition is driven by memories of three accidents: Three Mile Island in 1979, which killed no one; Fukushima in 2011, which killed one worker years later (the other deaths were caused by the tsunami and from a panicked evacuation); and the Soviet-bungled Chernobyl in 1986, which killed 31 in the accident and perhaps several thousand from cancer – around the same number killed by coal emissions every day.

Similarly with terrorism, our ability to make sensible decisions too quickly becomes eroded by fear and a desire for revenge. Pinker highlights that the worst terrorist attack in history was 9/11, which claimed 3,000 lives. In bad years, the United States suffers a few dozen terrorist deaths, a rounding error in their national tally of homicides and accidents. The annual toll is lower, for example, than the number of people killed by lightning, bee stings or drowning in bathtubs. Yet 9/11 led to the creation of a new federal department, massive surveillance of citizens and hardening of public facilities – and two wars which killed more than twice as many Americans as the number who died in 2001, together with hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and Afghans.

Even in the sanctuary of our own houses, we may become frightened when we hear that a third of all accidents take place in the home. We therefore tend to imagine our houses as especially dangerous places, without stopping to think that this is where we spend most of our time. Even if homes are not particularly dangerous, a lot of accidents happen to us there because a lot of everything happens to us there.

So how does the Walrus’s observation apply to all this? For me, it is the Damascene realisation that all these sorts of books are essentially the same and that I probably now know as much about amateur psychology as I am ever going to need to know. They are indeed, as my wife and daughter have often responded when I have shared ideas with them, largely a study of the blindingly obvious. As I have shown here, there were a few points I noted down as being of interest, but most of the anecdotes and stories were familiar from other books that I have read over the years, and there was little of novelty to engage me. I therefore think we are probably now at the end of this particular road and the time has come to explore other areas of the bookshop – goodness me!