It's Goodnight from Him

If a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, it presumably ends with one as well. If this is the first of my blogs you have read, or if you are someone who just dips into them from time to time, you will not have noticed how much time I have devoted in the last year or two to a single book, ‘Head Hand Heart’ by David Goodhart. If, on the other hand, you are a regular reader, you will probably share my view that it is time to move on now.

I have never actually checked, but I imagine that the notes from most of the books I read run to a couple of pages at most. Often, I can end with just a couple of paragraphs of ideas that I think worthy of sharing, but in Goodhart’s case there were nearly eleven sides, not far short of seven thousand words, which reflects how many of his ideas appealed to me – and the effort I went to in order to write it all down.

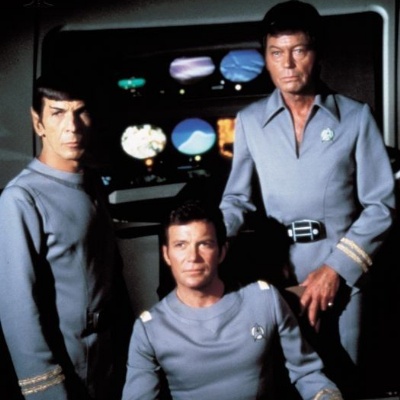

Anyway, this is the last time I will refer to this excellent book, not least because it ends with a reference to Star Trek, which is always a good place to bring things to a conclusion. Like so many wise commentators on the educational and political landscape, very little, if anything, will change as a result of a book like this. Almost all right-minded people know that our current systems have not been fit for purpose since at least the end of the Second World War, but there is no will to bring about substantial change, and education in particular remains depressingly low on the priority list of any of the people who might form a government in this country in the next few years.

As I reflect on my time in teaching, which started way back in 1988, it is hard to feel anything but disappointed about the lack of progress. The curriculum has hardly changed at all in the last thirty-five years, the examination system continues to favour those with the highest cognitive abilities and fails to recognise properly those whose skills are practical or compassionate. The focus remains far too narrow and schools almost invariably fail to prepare pupils for what the world is really like. I console myself that I have managed to make a difference by adding value to everywhere I have worked and improving outcomes for many over the years, which is good enough for me just now, but I probably should have shouted more loudly to try to bring about the sort of changes that David Goodhart advocates.

Politics, he writes, is an argument about what we value. Public life, just like private lives, can get things out of balance. In recent decades, public life has been too dominated by a cognitive class who have been trained to value the complex and quantifiable, and too often this has led to a narrow rationalism and economism. According to Google, over the last thirty years there has been a sharp increase in the use of economic words and a decline in the use of moral words: gratitude down 49%, humility down 52% and kindness down 56%.

In the summer of 2019, Goodhart says he heard David Miliband, the former British Foreign Secretary, talking about Brexit and, when asked whether Labour in power (1997-2010) might have contributed to the alienation expressed in that vote, all he could talk about was economic growth and inequality. There was nothing about identity or immigration, nothing about national sovereignty, nothing about the rapid change that makes many people feel that the past was better than the present. This exceptionally talented man seemed to have learned nothing about emotions in politics.

The American historian Christopher Lasch argued many years ago that a democratic society should not aim to create a framework for competition, where the most able succeed and the others fail. Yet this is precisely what we have achieved in recent decades as the ideology of meritocracy and social mobility, endorsed by the rise of the university-educated cognitive classes, have swept all before it.

Goodhart argues that competition is a vital force in inspiring innovation and challenging entrenched economic and political power. But too much competition and comparison at the individual level can generate a permanent state of anxiety and make it harder for people to align their expectations with their actual capacities – perhaps the best route to personal happiness. There will always be hierarchies of competence in all domains of human aptitude, and we need to preserve meritocratic selection procedures for important jobs, from running the country to captaining the local football team, while at the same time exploring ways of spreading respect and status more evenly.

Teaching, especially at primary level, he argues, is at least as much a Heart as a Head job. He says he is often struck by how many teachers he knows who talk about loving the children they teach, while sometimes finding them intolerable too. He tells of a friend who has become a primary school teacher in middle age and who says the best part of primary teaching is just building real relationships with the children. She says that to do the job properly, you have to love them, you have to become emotionally involved.

The latest research on good teaching confirms this. The head of the OECD’s influential PISA programme of educational assessment across different countries says that more important than curriculum content is the relationship between pupil and teacher. The child learns anything, everything, better when they think the teacher knows and cares about them. This is one of those things our grandmothers could have told us for nothing, and something our schools should try to reflect.

He makes the point that the feeling that a Head-dominated world does not pay sufficient attention to many of the things that really matter is one reason for the growing interest in mindfulness and meditation. For example, the number of yoga teachers in the US has been growing at more than 10% a year for several years. Paying attention is the essence of mindfulness, trying to see what is really of value – living slow rather than fast.

All children, the author asserts, should learn practical embodied skills in the crafts and arts, working not just with machines and ideas, but with actual materials such as wood, metal and fabric to make things that are both useful and beautiful. All children should be taught mindfulness and some form of spiritual exercise. They should learn some sort of practical life-skills, such as how to recognise cognitive distortions in oneself and others and how to mediate in disputes. These are quite practical things that can easily be taught – and transform lives.

The conclusion of the book understandably reinforces the gist of the argument, when Goodhart says that you might think that people with the fastest mental processes would bring more cognitive power to bear on reflection and therefore would be wiser; but voluminous research finds that raw intelligence and wisdom simply do not map to one another, at least not reliably. In fact, on some dimensions, such as wise reasoning about intergroup conflicts, cognitive ability and wisdom seemed to be negatively related. Wisdom often expresses itself in counterpoint to ideology. Whereas ideology pushes us towards certainty, purity and adversarialism, wisdom prizes humility, multiplicity and compromise. And it is a package.

In Star Trek, a recurrent theme is that the most blazingly intelligent character, the Vulcan Spock, lacks the instinctive empathy of Dr McCoy and the pragmatic decisiveness of Captain Kirk. None of the three alone is wise. Wisdom arises from the, sometimes tense, interaction of the triumvirate – Head, Hand and Heart brought into harmony on the Starship Enterprise. And if it is good enough for Spock, McCoy and Kirk, it is more than good enough for me. Beam me up, Scotty!