The Not So Wild West

Perhaps it is the time of year – spring cleaning and all that – or perhaps it is just a nagging doubt about loose ends, which I have always found disproportionately irritating, but I feel the urge to tidy. However, I also know that I just need to accept that no one can reach a point where everything is cleared away properly and permanently, and I would not be able to do this even if I were to employ Marie Kondo as my full-time life coach – which strikes me a truly horrible idea.

I say this because I keep going back to folders on my computer that have titles like ‘Unused Material’ or ‘Final Thoughts from…’ and then name of whichever author’s work I have not yet finished summarising. Regular readers over the years will have heard all this before about the need to finish one set of notes before starting on something else, along with the wholly unfulfilled promises to write shorter blogs and get to the point more quickly.

I therefore invite you to return to a book called ‘Past Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why It Matters’, by David Mountain, which I clearly found very interesting because I have written a lot of it down. It looks like we will need a couple more bites to get this book finished off, so we will start today with the author’s reinterpretation of some of what we think we might know about American history, we will finish before too much longer with some of his conclusions about why it is so important to ensure our knowledge of the past is accurate.

Few figures, Mountain tells us, are more enticing to the iconoclast than Christopher Columbus, a man who has become so swaddled in lies and legends – many the result of his own tireless self-promotion – that virtually every widely held belief about the explorer is wrong. Most obviously, he did not discover America. He never even set foot in what is now the United States, the country where he is most celebrated today. And he did not prove that the world was round. In fact, he was perhaps the last educated European, until a resurgence of flat-earthism in the nineteenth century, to argue that it was not round. He was not even called Christopher Columbus, but was born Cristoforo Colombo.

Mountain continues by saying that ultimately the question that is being discussed, debated, spray-painted and sledgehammered is: how do we commemorate the past? Do we celebrate it? Mourn it? Erase it? Ignore it? Do we commend the Age of Discovery as a time of daring exploration and geographic enlightenment, or condemn it as a prelude to imperialism and slavery? Do we praise Columbus as a champion of Italian-Americans or attack him as the murderer of indigenous peoples?

And it is here, the author argues, that the story of Columbus leaves the realm of history and enters that of politics. At best, he says, historians can present us with facts about the past, but they cannot tell us what to do with them. The facts about Columbus’s life have been known for quite some time, but the arguments rage on. His status as a national hero to some and abject villain to others virtually guarantees that Columbus will continue to be subject to biased, exaggerated and inaccurate histories for the foreseeable future. It will come as little surprise, Mountain reckons, if people are still trying to separate fact from fiction in another five hundred years.

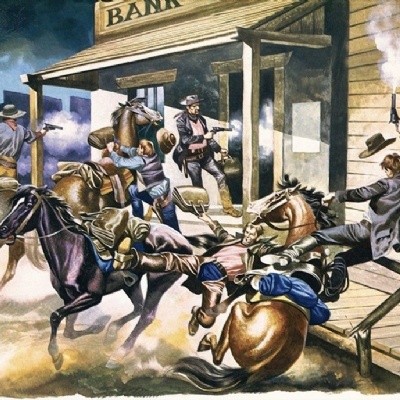

Moving to a later period of American history, we are told that popular conceptions of the American West owe more to fictional than historical accounts and, as a result, the reality of life on the frontier can come as a surprise to us today. Long-cherished notions about violence, lawlessness and justice in the Wild West are nothing more than a myth. For one thing, it turns out, those heading west had little to fear from attacks by Native Americans. The average American was more likely to see a wagon raid in ‘Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show’ than they were in real life. Indigenous people typically found it more profitable to operate bridge tolls and ferry crossings and sell supplies to emigrants than to murder them.

Apparently, when the historian John Unruh studied the history of the overland trails from 1840 to 1860, when an estimated 300,000 eastern emigrants crossed the continent, he found that Native Americans killed a grand total of 362 pioneers, and that pioneers killed 426 natives. When you factor in the tens of thousands of other fatalities suffered on these voyages, native aggression accounts for somewhere between one and four per cent of emigrant deaths. Pioneers were more likely to kill themselves accidentally with their own guns.

Nor was the frontier town a den of criminality, as is often portrayed in the movies. Customers at the bank, for instance, need not have worried about an impending robbery. Between 1859 and 1900 there were probably no more than a dozen bank heists throughout the entire American West. Bank managers were so unaccustomed to robberies that it was common practice to leave their vaults open throughout the day. Detailed studies of the records of frontier towns show that mugging, theft and burglary were also rare during this period, especially when compared to towns and cities in the eastern United States.

Even gun crime, the signature felony of the Wild West, was far less prevalent than is commonly assumed. Most men did own a gun, and fatal shootings did occur, just as they did in the east. But even in the most homicidal towns – places like Tombstone, Deadwood and Dodge City – relatively few met their end staring down the barrel of a gun. It turns out that only five murders occurred in Tombstone’s most violent year and in Deadwood the record was just four. More people were killed in the first fifteen minutes of the film ‘The Wild Bunch’ than in the first fifteen years of Dodge City.

Now in full flow, Mountain continues by saying that very few, if any, of these gunfights were the classic quick-draw duel of the silver screen. For one thing, most gun deaths took place not at high noon but late at night, usually in a saloon or gambling den, and usually when the combatants were more than a little drunk. For another, the handguns of the period were so inaccurate – being rarely able to hit a target more than eighty feet away – that speed gave you little advantage over your opponent. There are apparently records of shoot-outs in which both sides emptied their six-shooters at close range without managing to hit a single person. Perhaps most significant, however, is the fact that westerners were nowhere near as trigger-happy as they appear in fiction. As one inhabitant at the time put it, ‘Most men who carry guns like to get them out on slight provocation, but they are loath to use them. More than once, I have seen a whole crowd of men with their guns drawn but without a shot being fired.’

The author brings this section of the book, and thereby this week’s offering, to a close by saying that this did not mean that the Wild West was a haven of peace and tranquillity. It was, after all, populated mostly by young, unattached men, who are statistically the most violent people in any society. Coupled with the habitual binge-drinking and the prickly sense of honour common in nineteenth century America, it is little wonder that brawls were nightly occurrences in frontier towns. As well as fistfights and gunfights, there are accounts of people being attacked with knives, hatchets, chairs and even brooms. Outside the town limits, stagecoaches were routine victims of highway robbery, and an armed guard would often ‘ride shotgun’ with the driver. But even when this violence and criminality is considered, the American West was, for most people most of the time, a far more orderly, safe and sane place than the fiction it inspired.

If only the same could be said about the country today.